I have voted in every election (and I mean every election, even the weird February local initiative ones where you’re wondering why they saw fit to bring this up *now*), since 2000. I read the book that comes out, I do fact checks, and I vote.

There are some things I wish I could wave a magic wand and just have go away:

- Opinion Journalism. How you say what you say matters, and you can take a statement of fact and either amplify the parts of the statement that suit your need to sway an audience and/or de-amplify the ones that don’t suit you. We have forums for editorial journalism — they’re in the Editorials section, cleverly enough — and they should stay there. Since the dawn of “alternative facts” this has become more and more sketchy, and it feeds the hysteria.

- Speaking of hysteria – can we have a round of applause for the Hysteria Machine? No? Good. Because the Hysteria Machine is exhausting. Yes, I know s/he said the thing. It’s on tape, I saw it. I do not need you to reinforce to me how awful the thing is. All I need is the fact that s/he said the thing (or did the thing). Let me have my own disgust, or anger, or sadness, without imparting a healthy layer of *yours* on top of it. (By the by, I’m referring to articles, blog posts, radio, podcasts, etc. If you are my friend and we talk socially and you want to commiserate over the whatever — or even *healthily debate with facts and reasoning over differences of opinion* — then that’s cool.) I just don’t want a national news syndicate telling me where my outrage should come from. It’s insulting (it implies I don’t understand things and so wants to dumb it down to an emotional reaction) and it’s exhausting.

- Armchair data science. I love data. I love data science. I love everything about data including tracking it from where and how and under what rigors it is collected to the pipelines in which it runs to the output in which it is consumed. I love data even — and perhaps especially — when it disproves an assumption or bias I have, because learning is hard and sometimes un-fun and that means you are exercising your brain. Go brains! Armchair data science is none of these. Armchair data science is like this:

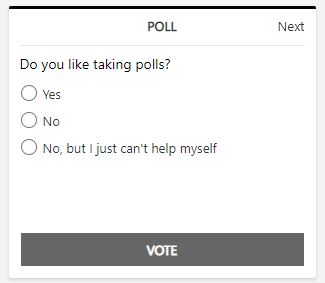

Let’s play a game. What’s wrong with this poll?

Firstly, it sits in a very popular media entry site, sandwiched between international news and Latest Video (of… stuff, I guess), below an article about free pastries at McDonalds and above local news (predominantly about COVID). The context is negligible or confusing at best. In what context am I being asked how I feel about polls? Apparently one in which I am also interested in a McDonalds Apple Pie while self-isolating and reading about how things are going far away from me.

Secondly, look at the nature of the question: “Do you like taking polls?” The question can be answered 3 different ways:

- Yes, I like taking polls.

- No, I do not like taking polls.

- No, I do not like taking polls, but I do anyway, because I can’t help myself.

The first one is easy – yep, like taking polls, so I’m going to check that box.

The second one has got to be facetious – if I do not like taking polls, I’m not going to take your poll. The results you get with this poll will not reflect the actual population that likes or does not like taking polls, and will skew heavily towards those that like taking polls. You’re not going to get the volume of “No’s” that reflect reality, because your poll does not have ESP and can’t read my mind as I register what it is asking me, reflect that I don’t like polls, and therefore do not engage. (The fact that I’m engaging this much on my blog and yet still won’t click your damn button illustrates this).

The third one is even better — I do not like taking polls, but I am unable to stop myself from grasping my mouse and clicking that button (or taking my finger and poking at it). What is being measured here is the impetus of the user to click a button because they like the little dopamine rush they get when they click a button; and likely has nothing to do with polls per-se.

The results of this poll will be useless — they will be heavily skewed towards the first and third answers, and, if the respondents who would represent the second one actually behave in the manner the poll suggests they behave, they would not be represented at all. What’s wrong with a useless poll?

This useless poll will probably drive someone’s decision, somewhere. It will either drive a marketing choice (have more polls! people love taking them!), an editorial choice (we should make polls on the front page every day!), or a behavioral choice (people love clicking things, let’s add more clickable content!). Which then will drive other behaviors and choices, and what you end up with are ad-filled, click-bait-filled pages of no material use for those of us who just wanted the facts.

This is just an innocuous, stupid little poll about polling. What happens when it looks like it’s a legit poll about how people feel about COVID? Or the economy? Or healthcare? Or personal freedoms? The output of that drives more of the hysteria machine, of course, because now we know how to cater to our clickers– they care about the economy so let’s tell them what is happening with it, but not objectively — let’s not share specific data points with a holistic view; let’s instead concentrate on the Stock Market. Or on the jobs data — but not all the jobs data, just the ones we think will drive the most clicks.

Ironically this means that those of us who would like all the data, so we can make informed choices, absent of editorial sway and anxiety exacerbation, have to click *more* … to dig it all out.